By Jade Westerman, Exhibitions Assistant at Palace Green Library

Our first step on the trail into the world of fairies was creating the exhibition Between Worlds: Folklore and Fairy Tales from Northern Britain. Between Worlds considered the various types of fairy folk that had existed in Northern British literature, history, and art. Our goal was to try to dispel the popular belief that fairies were pretty little creatures dancing at the bottom of the garden.

When we started this blog to run alongside the exhibition, we thought we would be prepared for all the weird and wonderful folklore and fairy facts that came our way. I’m happy to say that that was most certainly not the case…

Just as Between Worlds came to an end, so must this blog. For our final post, we thought we’d round it all up by telling you the top five fairy and folklore facts we found most interesting:

Folklore Fact No. 1:

Photography by Dwight Burdette: close-up of fairy door at Red Shoes, 332 South Ashley, Ann Arbor, Michigan, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fairy_door_at_Red_Shoes_Ann_Arbor_Michigan_close-up.JPG

Homes are a safe haven for many of us, and landscapes are sacred to fairy folk too. The consequences of trespassing on their land is dire and often deadly, depending on which stories you believe. Whether it’s from setting up camp, walking into a fairy ring, or crashing one of their parties, many unsuspecting mortals have been whisked away or had their lives threatened.

Even in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the unsuspecting humans find themselves the play-things of the fairy king and queen, Oberon and Titania, especially after waltzing into their woodland (see Prof. David Fuller’s piece on Shakespeare’s play).

One of the most prominent examples is Thomas the Rhymer, who played a significant role in the Between Worlds exhibition. The romance between Thomas and the fairy queen is famous, with many people regularly trekking to Eldon Hills to visit the location Thomas was gifted his prophetic powers. To read more about this extraordinary story, check out Dr Victoria Flood and Poppy Holden’s posts.

Folklore Fact No. 2:

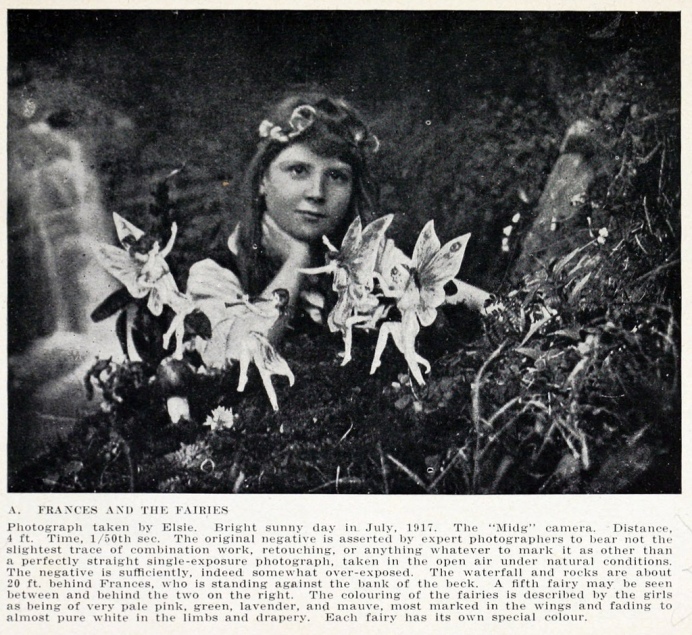

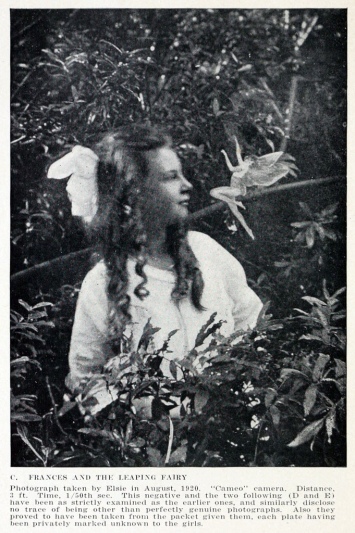

As folklore and fairy tales are rooted in the supernatural, it has been easy to manipulate them for one’s own purposes. Fairies have been the foundation of numerous hoaxes, including the famous Cottingley Fairies: a story of two young girls who nearly managed to convince the world of the existence of fairies.

Myths, folklore and fairy tales have always been a key tool for learning throughout history, and have often been manipulated for this purpose. One of the more surprising posts we received was on the adaptation of fairy tales by the Nazi regime. Many of the us know that there are variations of the story of Little Red Riding Hood, whether it’s the child-friendly or Brothers Grimm versions, but very few of us recollect a Nazi officer as the hero of that story. More on these sorts of tales can be read about here.

Folklore Fact No. 3:

Just as in our own human societies, fairy folk – both good and bad – have their own customs and etiquette too!

If you were to find yourself facing head-on with the Faerie Host, Andy Paciorek informs us that you should shout ‘God Bless you’! He also recommends throwing your left shoe at them (but if that doesn’t work, then you’re going to have to fight them with only one shoe on…).

We believe the general rule is try not to disturb them if you don’t need to. Don’t break a fairy ring if you ever come across them and, if you do want to draw a fairy in, then try using something shiny. But if you want to keep them away, then you should keep yellow flowers outside your house or have some iron objects lying around.

Read Pollyanna Jones’ eight tips on how to socialise with a fairy here.

Folklore Fact No. 4:

Groac’h or Water Witch. © Andy Paciorek

The prominence of certain fairy types differs from region to region. Here in Northern Britain, we have hob goblins, fairies who abduct children and adults alike, and even fairy folk royalty (see Rosalind Kerven’s post on the ancient fairies of Northern Britain), amongst many others.fairy folk royalty (see Rosalind Kerven’s post on the ancient fairies of Northern Britain), amongst many others. But then in Scotland, there’s the Seelie and Unseelie Courts, described by author and illustrator Andy Paciorek as good and bad fairies. In County Durham itself, there’s the Water Witch, which waits by the water’s edge, luring in small children to feast on their flesh and bones.

Illustration by Helena Nyblom for ‘The Seven Wishes’ from Among Pixies and Trolls (1913) by Alfred Smedberg, https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pixie_(folletto)#/media/File:I_samma_ögonblick_var_hon_förvandlad_till_en_underskön_liten_älva.jpg

Our friends at the Museum of Magic and Witchcraft explained that Cornwall has a variety of fairies, but their most prominent is the piskie. The piskie runs rampant causing mischief and mayhem along its path. Like most fairies, in order to fend the piskies off, you need some iron. Otherwise, they’ll steal anything shiny and play tricks.

Special Collections and Archives at Cardiff University also had an folklore exhibition running at the same time as ours here at Palace Green Library. Lisa Tallis explained that they wanted to focus on the darker side of Welsh folklore, looking at demons and devils. She speaks of fairies such as the Bendith eu Mamau (Their Mothers’ Blessing), who are known to both bless favoured humans and steal new-borns from their beds.

Folklore Fact No. 5:

Folklore and fairy tales aren’t just a thing of the past or creativity to be inspired by the fairy and mythological folk. They still inspire people today, from writers to musicians to artists.

Many authors who have contributed to this blog are still inspired by the stories of fairy folk (the list of authors and their blogs can be viewed here). Adam Bushnell discusses in his post a few modern works that have used folklore and myth as the foundation of their narratives.

The Brothers Gillespie performing at Palace Green Library Cafe ©Ross Wilkinson

The Brothers Gillespie performed for an audience here at Palace Green Library, playing many songs inspired by the folklore they’ve accumulated on their travels. They’re influenced not only by the likes of Nick Drake and other modern musicians but also the folk songs and fairy tales of old. Many singers today still perform the traditional folk ballads, such as one of our contributors Poppy Holden.

The enchanted atmosphere and landscapes the fairy tales create provide some fantastic photo opportunities (read James Brown’s blog on his ventures into the fairy landscapes of Melrose, Aberfoyle, Middridge and Inglewood):

We hope you’ve all enjoyed reading this blog as much as we enjoyed putting it together! However, we couldn’t have done it without the help of all those who made some fantastic contributions:

- Francesca Bihet, PhD Candidate at the University of Chichester.

- Kevan Manwaring, Teacher in Creative Writing at the University of Portsmouth, Open University, and University of Leicester.

- David Fuller, Emeritus Professor of English at Durham University.

- Rosalind Kerven, folklorist and author.

- Judith Hewitt, Museum Manager at the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic.

- Victoria Flood, Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Literature at the University of Birmingham.

- Icy Sedgwick, blogger and author.

- Adam Bushnell, author.

- The Brothers Gillespie, professional musicians.

- James Brown, Science Communicator and photographer.

- Lisa Tallis, Assistant Librarian of the Special Collections Archives, Arts and Social Studies Library, Cardiff University.

- Poppy Holden, professional singer and singing tutor.

- Laura Coulson, fairy and folklore blogger.

- Andy Paciorek, author and illustrator.

- Pollyanna Jones, author.